Ben Huff

“I first saw Camp 17, on the 15,000-square-mile Juneau Icefield, from Juneau’s Blackerby Ridge in the summer of 2011 or 2012. As a photographer who has done a lot of work with architecture and people on the edge of wilderness, I was really interested in the space visually. Those shiny tin can buildings surrounded by ice had a real effect on me. I came back to town to find that not a lot of people knew what was going on up there on the icefield.

Once I found the Juneau Icefield Research Program, I reached out to them through Deb Gregoire, who's a friend, and was the local manager at the time. I really wanted to get up there and see what it was all about. I was driving her crazy. She eventually agreed to let me tag along for staff training for two days and make pictures. They had a staff member who was showing up late and he hadn't been up there before. So she asked me to hike him up via Blackerby, stay with the team for two days, and then hike down via Lemon Creek. And I would make pictures for them.

I stayed with them for three days and was smitten with the whole idea of this little community starting off at sea level in Juneau and hiking up through the bramble and Blackerby, and across this immense span of ice and ending up in Atlin, British Columbia, across the icefield. I was enthralled with the whole prospect of that: traverse, and field work, and students in that landscape for the first time.

It was good timing—they were beginning to think about art and storytelling as a component of the program. Eventually, along with artist Hannah Mode, I carved out a little spot for myself as part of the science communication faculty.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

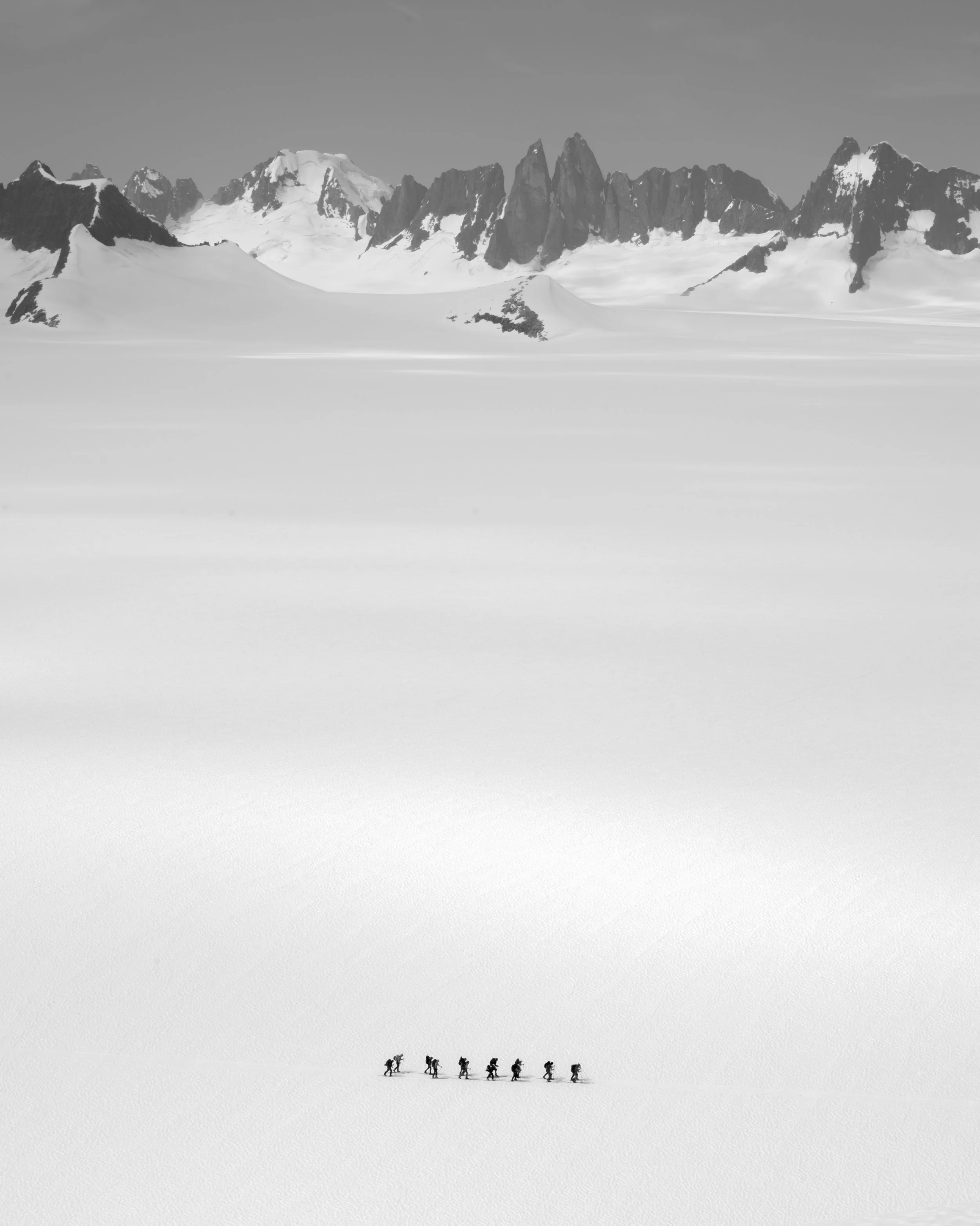

“This will be season six for me with the Juneau Icefield Research Program, going up for two- or three-week stints every summer. It's a remarkable program of 30 to 32 students every summer who are embarking on—whether they know it at the time or not—this life-changing experience.

Some of them have never been on a glacier before. Some of them have never been on skis before. We march them up to Camp 17 and put them on skis and then send them towards Atlin. Of course, it isn’t that simple, but there’s an urgency and energy to it that feels that tenuous and exciting.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“2022 was my first time at Camp 10 for any great deal of time. My wife, Deanna, and I did the traverse across the Juneau Icefield backwards a few years ago. But, we skied by there during a whiteout. And, I’d flown over Camp 10 making aerial pictures, but I hadn't been in camp before.

Being at the divide at the top of the Taku and looking down into the valley on a clear day, you can see a sliver of water. Most days it’s shrouded in a layer of clouds. But to be up there with the glacier below and miles of ice down to the inlet, and to have that experience of talking to students from all over the world about the landscape and the geography of the space is really powerful. The landscape is overwhelming, but in talking about it we can make it knowable. I take great joy in looking at maps and thinking about where we're at in the movement of ice and water down slope into that drainage and talking about fish and people downstream and Juneau and that whole system. It’s incredible.

The Juneau Icefield Research Program itself has been around for 77 years, but we're still learning things. We're always trying to do better from a local storytelling perspective, a Native storytelling perspective. We’re constantly trying to connect the students with a larger landscape and geography and the impact that's beyond our immediate landscape.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“Dea and I moved to Juneau in the winter of 2010. I was still teaching at Fairbanks, and on contract to teach that next semester. So, we drove down December of 2010, and I went back to Fairbanks until May of 2011.

We moved to Fairbanks in 2005 for Dea to go back to school. We thought, at the time, that she would get her Ph. D. in atmospheric chemistry and then we would go back to the Lower 48. Maybe I'd go back to school, get my MFA and teach somewhere out West. But, it wasn't long in Fairbanks before we knew we were in trouble. We loved the place too much to leave.

We followed a job to Juneau, thinking we’d end up back in Fairbanks. But, in Juneau we found everything we were looking for. The closeness of the mountains and the water makes this place really special to us. I miss the north a great deal at times, but not enough to leave Southeast. I can’t live landlocked again.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“I’ve fished from the shore since that first summer here. Countless days standing on a rock in the rain somewhere down Thane. Dea and I talked about buying a boat for years. Then COVID hit, and Dea and some friends started developing the climbing at Jaw Point, at the mouth of the Taku. The focus there, and the uncertainty of the pandemic, made it seem like bobbing around in Taku Inlet was the safest place to be.

The whole world changed when we got the boat. We’ve spent a lot of time with friends, fishing from their boats, out of Auke Bay. But the south side was new. On countless days I’d drop the climbers at Jaw Point in the morning, fish all day, and pick them up in the evening. So, Jaw was sort of the start and end of my fishing day. This meant that my focus was closer to Taku Inlet than maybe I would have otherwise fished. Figuring out the unique particulars of a spot on the chart is such a satisfying endeavor.

That's kind of the way that I've always worked photographically too. I find a little place and dig in. I begin to know the little idiosyncrasies and the characteristics that make it unique.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“In the last couple of years I began thinking more about the flow of fish headed up the Taku. Moving a little bit further up the inlet, where they might be pulled up when the tide’s going out, and where they might be idling. It wasn't more than a mile in any direction, but reengineering my mind and the way that I was thinking that maybe fish were moving and following them.

I hadn't spent a lot of time on that south shore from Greeley Point and across to Cooper. It's a really small landscape, but even though it's right there, it wasn't somewhere that I had spent a lot of time. I’d normally hustle past on my way to the fishing grounds. You can get to know a place intimately as it glides by at three knots.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“On the very last day of the season, I spent some time aboard Tyson Fick’s boat with him, his son, and chef Beau Schooler, making pictures. The three of them fishing and me making pictures. Kind of wishing that I was fishing with them.

For the past few years I’d been weaving in and out between the gillnetter fleet’s nets, taking the crew to Jaw Point. And, fishing the same grounds, or close by, between their openers. There’s an inherent romanticism around commercial fishing in the silty waters of southeast Alaska. In my younger days, if I had grown up here, no doubt I would have spent time working on a boat.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“In 2022 I had the opportunity to do a large section of the traverse of the Juneau Icefield with the Juneau Icefield Research Program students. I hiked up to Camp 17 two days before trial parties began leaving camp for their ski to Camp 10. It takes two days to get to Camp 10, with a night at Norris Cache, above the Norris Icefall on the way. The route takes students and staff from Camp 17, down the Lemon Glacier, up over by Nugget ridge down into Death Valley and up the North Icefall on the first day. There's a spot above the icefall with a temporary camp for the night. The next day is a long push on the Matheis Glacier to the Taku Glacier and the nunatak of Camp 10.

Geographically and on the calendar, it’s roughly the halfway point of the traverse, and the physical high point. By many people's accounts, it’s one of the nicest camps. There’s just this energy and optimism, and relief, from the students that they’re survived the two day ski.

The difference between Camp 10 and 17 is striking. The lights from town are long done. So are the trees and the faint smell of salty air. Scale is difficult to discern and the quiet makes some uneasy.

A lot of the students come with glacier background. Some of them know the landscape, some of them don't. I fall somewhere in between. As faculty, part of my role is to help facilitate different ways of seeing and communicating what they’re seeing and experiencing in the landscape. Truth is, I'm going through the same exercises. I’m as transfixed and stunned by the place as they are. I struggle for words, pictures, and ideas that can rise to the occasion.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“The icefield has opened up to this unbelievably complex space for me visually. It’s a 15,000-square-mile sheet of ice that stretches from Taku to Skagway to the Mendenhall to B.C, which feeds over 200 glaciers in the Southeast. It’s been there as long as time, and somehow I’ve just begun a relationship with it. This small dot in a constellation of other stories, pictures, and endeavor.

To live in Juneau, and to be an artist here, is to live with the remnants of that landscape. The silty water that runs ribbons around my fishing line in Taku Inlet originated beneath the buildings at Camp 10. The U-shaped valley that is the Taku Glacier slowly churning downhill. Getting smaller by the drop.

This is a landscape and story that I feel really fortunate to have a small part in telling.

JIRP has 77 years of history and models that will project 77 years in the future. The research that’s being conducted on the icefield is of vital importance.

To spend time up there with students who are deciding about making that landscape, or similar landscapes, and climate, science, or advocacy, what they're going to do with the rest of their lives is a privilege. They’re committed and thoughtful and brilliant.

I'm learning as much from them as I can possibly believe that I'm giving to them. It was as much about the program and the landscape giving us a space for that to happen, without having any phones and access to the outside world for a while. To just be present and to have conversations and to think deeply about the landscape.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“Being in the elements and places that are sometimes austere—photographically, I'm comfortable in those places. In Fairbanks, everything's sort of horizontal. You go to the north slope, get out of the mountains and everything's flat—other than the architecture and the people, which break it up.

In Juneau, everything's trees, mountains, and sort of a vertical. Then at the ice field, much is flat again. The thing that I struggled with the most, which makes it such a unique landscape, is that it's very close to monochromatic. It’s blues and it's whites and it's grays.

When I started making pictures of each student—four-by-five formal portraits with the large-format camera—I made those portraits in black-and-white to level the playing field. To give them some space to command the frame and to take away anything that was visually busy and make it about the eyes and about that gaze. I was crossing those black-and-white portraits with color landscapes. Over time, I'd look at those color landscapes and see them as black and white compositions. So I made a decision to strip away the color. Visually, it just demanded it. There's a timeless quality to black and white. I like that it’s more difficult to nail down the time.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“The landscape is changing so fast—even in the last couple of years. When students leave Camp 17, they’ve always taken the same route out of Lemon Glacier to get over to Nugget. In 2019, the staff had to change the route getting out of the Lemon Glacier because there wasn't enough snow. So for 74 years they've been going the same route every year and now the route has changed. The program itself, the timing has changed.

People who have been around a long time will once in a while say, “Why isn’t JIRP in the Fourth of July parade anymore?” It's because the program is starting earlier because there's less snow and ice. Everything has to go earlier.

We used to hike to Camp 17 via the Lemon Creek Trail. It was a potent ecology lesson — starting at sea level, up through the forest, into a glacial cut valley, and finally to Ptarmigan Glacier. We can see the way the icefield is changing, and thinning, through data, but the anecdotal and visual changes yearly are coming at an accelerated rate.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“On the icefield, the glaciers we stand on are feeding this system that supports all five salmon species. Jobs and households and livelihoods and millennia of salmon have been spawned in that river, gone out to the open ocean, come back, and created more salmon. It’s not lost on me that always talking about the salmon in the present tense is not a given. I don’t want to come a day when, talking about the migration of Salmon back to the Taku, I say ‘there used to be a time…’

We’ve made decisions that were based on greed and based on things that didn’t consider future generations, other than putting money in a few people's pockets. We go from telling stories of what is, and what our history is, to telling stories about something that we used to have. I think there will inevitably be a lot of those stories in this state.

To tell those stories as something of the past seems incomprehensible.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor

“My hopes? I’ll go back to that little piece of the Taku Inlet, a small stretch along Cooper Point.

My niece and nephew come up every other summer or so. And they love going out fishing.

My brother and I grew up during a time when parents would push us out the door in the morning, and ring the bell to call us back home at dinner. We’d come home with scraped knees after mucking around outside all day long.

I'm sure my niece and nephew have probably put a line in the water for a catfish over the years in the Mississippi back home in Iowa. But they haven't really had that experience. It's been amazing taking them out fishing here. Away from their phones and life back home.

My nephew was up three years ago, and got a bunch of coho. Then my niece was up last year. She caught a nice king on the seventh of June, which was bigger than any fish that her brother caught. She was absolutely over the moon. I think it was the biggest fish we caught on the boat all year. And now my nephew can't wait to come back and get a bigger fish than his sister.

I’d love to be 80 and take my grown nephew out with his kids. We’d find a monster king near Cooper Point. Tell stories of past years of fish caught and lost. And, be confident that his kid’s kids, and their kids, will have the opportunity to have that experience along that small strip of shore downstream from the Taku.”

—Ben Huff, Juneau-based photographer, Juneau Icefield Research Program instructor