Bear man of Admiralty Island Allen Hasselborg — and Climate Change

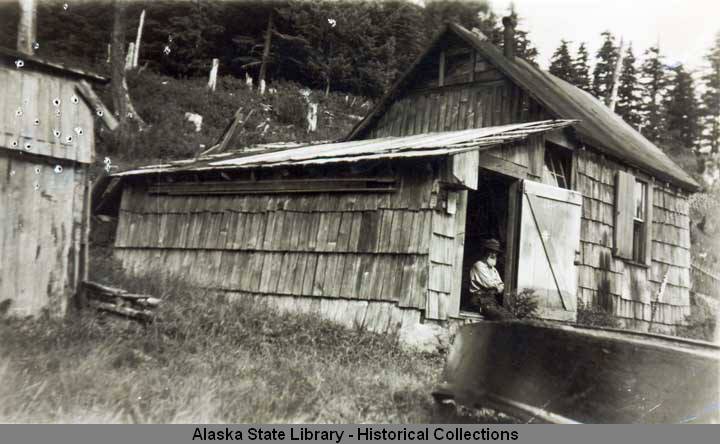

Allen Hasselborg at his cabin on Mole Harbor on Admiralty Island. He kept meticulous weather journals for decades. Alaska State Library Historical Collections.

Every day for decades, bear hunter, guide, and early 20th century Southeast Alaska homesteader Allen Hasselborg logged the temperature, rainfall and weather at Mole Harbor, on Admiralty Island in Southeast Alaska.

Now, almost a century later, University of Fairbanks student Emily Williamson and UAF PhD candidate Chris Sergeant have a new study out that uses Hasselborg’s years of meticulous record-keeping to show the small-scale accuracy of a large-scale climate change model.

From left to right, Ryan Bellmore, Chris Sergeant, Bill Johnson and Michael Humling at Big Shaheen Cabin, which was first built as the base for a scientific expedition for which Allen Hasselborg was a guide in the early 20th century. It was shortly after this trip that Sergeant, a scientist, read “Bear Man of Admiralty Island” and became interested in using Hasselborg’s weather journals to test the accuracy of climate change models. Photo by Michael Humling.

Sergeant took interest in the possibility of the study after paddling the Cross-Admiralty canoe route, which traverses a series of lakes and portages across Admiralty Island (Kootznoowoo, or, roughly translated, “Fortress of the Brown Bear, in Lingít) from Mole Harbor to Angoon (Aangóon, or “Isthmus Town”).

“After the trip, I read ‘The Bear Man of Admiralty Island,’ and there was a passage about how he (Hasselborg) kept a detailed weather journal,” he said. “I went to the state archives, found the weather journals, and sure enough, there was a lot there. But it’s also a lot of work to reconstruct, so I started looking around for someone to help me out.”

He sent out an email to a UAF list-serve, and Williamson, who will graduate from UAF with an ocean science degree in 2022, took an interest.

After coming on board, Williamson scanned the journals, reading them and learning about Hasselborg along the way.

Allen Hasselborg in a skiff in 1932. Alaska State Library Historical Collections.

He “had quite a sense of humor,” Williamson said, and would write a couple words describing what he was doing with his day along with his data. “Hay,” for example, if he was collecting dry grass for his garden. Or “Bulldog,” which was the name of his boat. He had a one-word shorthand for “shot a bear.”

He also had a habit of writing his responses to a book’s author in the margins. Some of those were to the point.

Allen Hasselborg at his cabin on Mole Harbor on Admiralty Island. He kept meticulous weather journals for decades. Alaska State Library Historical Collections.

He guided John Holzworth, the author of “Wild Grizzlies of Alaska,” for example, and his copy of the book shows he didn’t think too highly of the book or the author.

During a section in which Holzworth said the country he and Hasselborg had walked through was “rough and broken,” Hasselborg crossed it out and wrote “crybaby.”

“Rot” and “fiction” were other common reactions — and “fiction” was his reaction to the book’s portrayal of himself.

“He was really committed to facts, and facts being really exact,” Williamson said. “He would annotate all of the books he had if he thought they weren’t exactly correct. It’s kind of fitting I’m using his data to fact check a model.”

After Williamson did the work of inputting the data, she and Sergeant were able to look into the accuracy of the model they chose: “Climate NA,” (short for “Climate North America”).

“It’s easy software to use,” Sergeant said. “You click on a point on a map, and it generates a lot of data for you.”

It was data that they found accurately predicted temperatures and rainfall amounts in Southeast during the years Hasselborg kept daily records: 1926 to 1954, years only seven weather stations existed in the region.

Climate models, and verifying local accuracy, is important not just for predicting climate changes, but all they impact. Snow and rain estimates are often used to gauge stream flow. And, as the paper notes, salmon populations’ success is closely tied to stream flow, so “having access to high-quality climate information is critical for resource managers and users to assess habitat conditions over time and the potential for future change.”

As a mountainous, glacial environment, Southeast Alaska is especially challenging, the paper notes.

A brown bear in Mole Harbor, at the beginning of the trail system on the Cross-Admiralty Canoe Route. Photo by Bjorn Dihle.

“Climate change is occurring rapidly in Southeast Alaska…. A key challenge is determining the rate at which these changes are occurring, thus it is important to compare contemporary climate trends with historical data sets… This is especially challenging in topographically complex areas like Southeast Alaska, where mountains rise from sea level to hundreds of meters above sea level … A mosaic of mountains, glaciers, and narrow marine passages create dynamic micro-climates combining wet and mild coastal zones with drier and colder continental conditions,… making it difficult to discern the accuracy of downscaled climate patterns relative to nearby weather stations,” reads the paper.

“It’s so cool to be able to paw through these journals with our own hands, and then use it for science,” Sergeant said. “And to think that someone just going out and taking the temperature every day, and looking at how much rain fell, they can contribute to climate change research almost 100 years later.”

Chris Sergeant paddles in the rain while on the Cross-Admiralty canoe route trip that inspired the study. Photo by Bill Johnson.

“Snoop around your own local libraries and archives for the same thing, because there are really rare opportunities to help out scientists who are studying climate change,” Sergeant said. “The more we can dig up weather journals like this, the better we can confirm models of historical climate and how fast climate change is occurring in our environment. I think there are probably a lot of treasures out there like this.”

The article is available to read free of charge here: https://peerj.com/articles/12055/

Sunset at Beaver Lake. Photo by Michael Humling.